How a theology student experienced the liturgy of Jerusalem

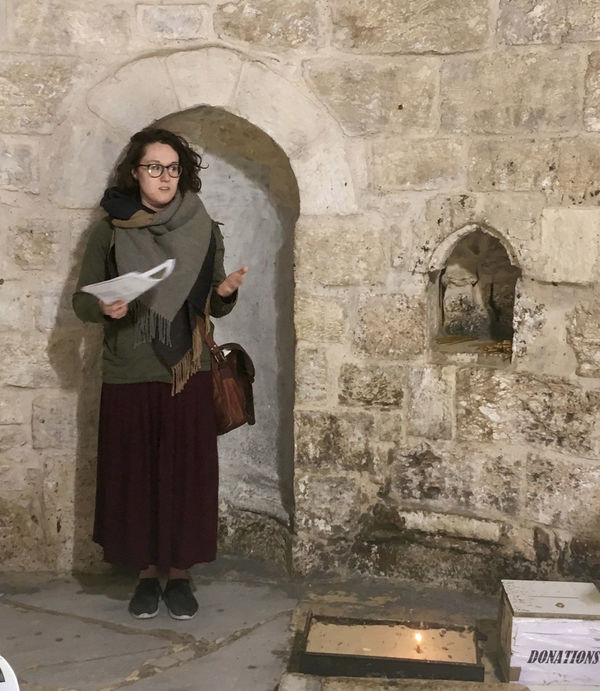

Andrea Antenan Peecher presenting at the Chapel of the Ascension.

Andrea Antenan Peecher presenting at the Chapel of the Ascension.

Andrea Antenan Peecher is a first year master of theological studies student with a concentration in liturgical studies. She is originally from Springfield, Illinois and completed her undergraduate studies at Hope College in Holland, Michigan. Before attending Notre Dame, she lived and worked in New Jersey. Peecher traveled to Jerusalem as a part of a theology doctoral seminar titled “Liturgy, Sacred Space, and Identity in Jerusalem,” led by Nina Glibetic from the department of theology. She reflects on how an experience at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher allowed her to expand her research interests.

Benedictine Monk and archaeologist Fr. Bargil Pixner once called the Holy Land the “Fifth Gospel” and said that by “reading” the Holy Land, “the world of the four will open to you.” After visiting the Holy Land, I would humbly add that an experience of the Holy Land will open not only the biblical accounts of Christ’s life, but also the liturgical life of the Body of Christ. And indeed, this was the purpose of our seminar’s trip to Jerusalem—to experience the liturgy of Jerusalem in conversation with the topography and to unlock meaning we cannot access in a classroom in South Bend. Many of my experiences in Jerusalem vivified my study of ancient Christian liturgy, informing and recasting my research interests. However, one experience touring the Church of the Holy Sepulcher stands out, as it connected directly to the research I did in preparation for the course.

Halfway through our week in Jerusalem, Dr. Joseph Patrich, a distinguished scholar and archaeologist, took us on a guided tour through the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. We squeezed through throngs of pilgrims to consider structures visible to the naked eye, but we also gained access to more ancient material which is locked behind doors that scurrying tourists passed over. Our group stood quietly as a monk with an oversized set of keys unlocked these doors for us. Just behind them were the architectural remains of the church structure built by Constantine in the 4th century—a structure that has been the backdrop of much of my own research for our class.

Notre Dame theology students visited the Old City of Jerusalem from a viewpoint on the Mount of Olives.

Notre Dame theology students visited the Old City of Jerusalem from a viewpoint on the Mount of Olives.

In our coursework before we left Notre Dame, I researched late-antique baptismal practices in Jerusalem and presented a paper to my class. My research showed that the physical space of Constantine’s church—the baptistery, the Anastasis, and Golgotha—was essential to baptismal practices in Jerusalem. As we examined the ancient remains in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, I mapped the Constantinian basilica in my notebook, connecting the structures I saw to the concepts I had studied at Notre Dame. With Dr. Patrich, I also discussed the location of the Constantinian baptistery, which has been a matter of some debate. I have since become very interested in the archaeological evidence for the baptistery and have corresponded with Dr. Patrich since returning from Jerusalem. Prompted by access to archaeological remains and contact with a talented scholar, I have already been able to expand my research and apply what I learned in Jerusalem.

Before visiting Jerusalem, my research lacked a certain understanding of the physical space on which it relied so heavily. Even though I had pored over maps and textual descriptions, the reality of the space was distant and disconnected. Our tour with Dr. Patrich was but one of many instances which merged my conceptual understanding with the spatial reality of Jerusalem. Now, when I read the baptismal lectures of a 4th century bishop of Jerusalem, I can envision the apse he stood under while lecturing the catechumens and am familiar with the topography he integrates into his theological exhortations. This knowledge of physical space is essential in liturgical study because liturgy is not a two-dimensional theological text. Liturgy is enacted in and interacts with sacred space, objects, and people. And in order to understand the liturgy of Jerusalem—ancient or otherwise—we had to “read” the Holy Land. By seeing and experiencing the history and liturgy of Jerusalem, the world of Christian history and liturgy opened to me. As it opened, so too did new insights and research interests that I am eager to carry into my scholarship, life, and faith at Notre Dame.